Photo Credit: Bjaglin

Each year on the Saturday before Ash Wednesday, the usually sleepy Oruro comes alive, hosting the world renowned Carnival. The unique festival features spectacular folk dances, extravagant costumes, beautiful crafts, lively music, and up to 20 hours of continuous partying.

A party like no other, Oruro Carnival is Bolivia’s most sought after tourist attraction, drawing crowds of up to 400,000 people annually. Whilst the festival is celebrated throughout most of the country, Oruro is without doubt the most popular, offering a memorable experience for all those involved.

If you’re lucky enough to be in Bolivia at this time of year, Oruro Carnival is one fiesta not to be missed!

Contents

History of Oruro Carnival

Photo Credit: Álvaro

Long before Spanish settlement, the ancient town of Uru Uru (the pre-hispanic name for Oruro) was a religious destination for the Aymara and Quechua people of the Andes. Locals would worship Andean deities, praying for protection and giving thanks to Pachamama. The Uru people also revered their gods by celebrating Ito; the religious festival from which Carnival is thought to have originated.

In 1606 the Spanish founded today’s Oruro using the land, already being mined by the Indigenous population, as a base for obtaining the rich minerals in the surrounding hills. In conjunction with their land being taken away, the locals were used as laborers for the Europeans who encroached on their religion with the introduction of Christianity.

From the get-go, Spanish priests tried to ban the Uru Uru rituals and traditions. Not wanting to renounce their beliefs, the Indians observed their traditions under the guise of Catholic rituals in order to keep their new overseers happy. The catholic priests frowned upon this, but tolerated it in order to convert the Aymara and Quechua people to their religion.

In a further attempt to convert the locals to Christianity, priests encouraged the Indians to perform their traditional dances and music in line with Catholic holidays as well as transform their festivals into Catholic rituals; a prime example being the festival of Ito.

Photo Credit: CassandraW1

By the mid 18th century, Andean rituals had morphed into Catholic observances, giving birth to the religious celebration we know today as Oruro Carnival.

After Bolivia gained its independence from Spain in 1825, Oruro’s aristocracy distanced themselves from the Indigenous population, each group holding their own Carnival celebrations. With the rise of socialism in the 1940s, the upper class came to see the Indigenous culture and lifestyle as the the ideal model for a well established society. Seen as a matter of national pride, Oruro’s upper and middle class began to form their own dance groups based on the traditions of the Andean culture.

Today, Carnival is a complex interlacing of Catholic ideals and ancient pagan expression, reflecting the diverse aspects of Oruro’s rich cultural history.

Meaning of Carnival

Using a mix of dance, music and costume, Carnival not only tells the story of how the Spaniards conquered the Aymara and Quechua people of Bolivia, but celebrates good versus evil along with Oruro’s rich cultural identity.

The world Carnival is derived from the Spnaish word carne levare, which means “take away the meat”. This is in reference to Lent, the 40-day period in which devout Catholics abstain from consuming meat in the lead up to Easter. Since a reported 90% of Bolivians call themselves Catholic, the word was used to signify Carnival; the 10 day festival leading up to Lent.

In Oruro, locals believe Carnival commemorates a miraculous event that occurred in the early days of the town. Story has it that the Virgin of Candelaria took pity on a fatally injured thief by helping him reach his home near the silver mine of Oruro before his death. When the miners discovered the man’s dead body at the base of the mine, there was an image of the Virgin hung over his head.

Photo Credit: José Porras

The story is believed to have been concocted by the Spaniards in order to convince the Indians that they needed to dedicate a church to the Virgin. The ever religious Indians followed the recommendations of the Spanish by painting a mural of the Virgin Mary and worshiping her in a 3 day festival held the same dates as the Indigenous celebration of “Anata”.

Since the miraculous event, Oruro Carnival has been observed in honour of the Virgen de la Candelaria or Virgen del Socavon (Virgin of the Mineshaft) and the Sanctuaria del Socavon (Church of the Mineshaft) is where the carnival’s most important events are held.

The dances of Oruro Carnival are based on the legend of Virgin del Socavon, combined with the ancient Uru tale of Huari and the struggle of Archangel San Miguel against the Devil and the seven deadly sins.

Bolivian Life Quick Tip:

As voted the best way to travel around Bolivia and Peru, we highly recommend choosing Bolivia Hop as your means of transport. Their safe, flexible and trustworthy service have proven to be the best way of getting the most out of your time in South America!

The Icons of Carnival

Photo Credit: Szymon Kochański

Carnival sees a blending of Catholic and Indian rituals, mixing the Virgin and Devil teachings of the Catholic religion with the Indian ideas of Pachamama and Tio Supay.

El Tio, the most recognised icon of Carnival, is a malevolent character who transforms into the Devil for Carnival. Known as the Uncle or God of the mountains, indigenous miners believe El Tio is the owner of the mine’s minerals and the overseer of their safety. In the hope he won’t get angry for taking his precious metals, during carnival, miners dance and leave gifts of beer, food, cigarettes and coca for El Tio.

Pachamama is the Earth Mother who the Indigenous people believe is a giving and benevolent goddess much like the Virgin de la Candelaria.

Other notable icons in Carnival include the following:

- Archangel San Miguel

- Incas

- Spanish Conquisadors

- Tobas warriors symbolising the victors of the Inca Empire

- Caporales represening the overseers who gained a reputation for their cruel treatment of Indian and slave laborers

- Morenos representing the Africans who were enslaved by the Spanish back in the 1600s.

- Kallawayas representing doctors of the Inca empire

- Llameradas representing the pre-Columbian story of the llama herders who danced to maintain control of their herds

FIND OUT WHY

FIND OUT WHY

The Carnival Experience

Photo Credit: Wakusrgh

Oruro Carnival beings with a ceremony dedicated to the Virgen del Socavon where marching bands play raucously to greet the Virgin.

Two days before the main Carnival event, Anata Andina is celebrated by locals who give thanks to Pachamama for the wealth of agricultural produciton she has provided them. One hundred groups from all around Bolivia participate in this event, showing off their native music, dances and costumes.

On Friday night a soirée takes place in dedication to El Tio, covering the whole route of Carnival until the wee hours of the morning.

The following days – Pilgrimage Saturday, Carnival Sunday and Devil’s Monday – take place during a three day / three night parade featuring over 50 groups of folk dancers, 150 bands and 10,000 musicians. Saturday is the main parade day with the procession covering a four kilometer route lasting up to 20 hours.

Every year the parade is lead by the colorful representation of Archangel San Miguel wearing a blouse, short skirt, sword and shield. Following San Miguel are the iconic devils and a host of bears, pumas, monkeys and condors; symbols of the Uru mythology. The most elaborate costume is worn by the chief devil, Lucifer, who dances with other devils at his side as well as China Supay, or devil women, who attempt to seduce San Miguel with their dance. At the end of the dance troop are the “seven deadly sins” pride, greed, lust, anger, gluttony, envy and sloth.

Photo Credit: Mark Bellingham

Surrounding the devils are other dance groups portraying local worker unions, ancient Incas and the black slaves who were brought over by the Spaniards to work in the mines. Following these groups are bejeweled vehicles carrying offerings for the sun god Inti, and precious minerals for El Tio as well as Inca characters and a group of conquistadors.

The parade finishes at Oruro’s soccer stadium with the enactment of two plays, the first one about the Spanish conquest and the second about San Miguel’s battle with good and evil. During the second dance, the angels kill seven devils each representing the seven deadly sins. Once this is done, Pachamama emerges, however is set upon by the angels also. She begs for forgiveness and is eventually pardoned by the angels

Early on Sunday morning, after San Miguel gains victory over the demons, the dancers return to Santuario de la Virgen del Socavón where they pay homage to the protective “Virgin of the Mine”. During the afternoon there is another parade, albeit much smaller, featuring more music and dance displays.

Photo Credit: Szymon Kochański

On Monday the devils break away into smaller groups, dancing around huge bonfires. The next day, Shrove Tuesday, is dedicated to family reunions and cha’lla, a ceremony of thanks to Pachamama . Wednesday sees people flock to the surrounding countryside to make offerings to Pachamama at the four rock formations – The Toad, The Viper, The Condor and The Lizard.

The Monday after Ash Wednesday marks the culmination of the festivities with Dia del Auga (Day of the Water). This playful day involves a massive water bomb fight in which gringos are the primary target!

Dances and Costumes

Photo Credit: Rasmus Thornberg

Oruro’s fascinating history, diverse culture and religious influence is most apparent in the endless stream of folk dances performed during Carnival. Over 50 folkoric groups made up of around 20,000 dancers participate in the festival representing the various indigenous groups throughout Bolivia.

The most famous of the folk dances is without doubt La Diablada or Dance of the Devils, a ritual representing the victory of good over evil and one that has remained unchanged since colonial times.

Performed for the first time in 1904, La Diablada was born out of the Indigenous miners fear that El Tio, the god of the underworld, would be jealous of the attention they were paying to the Virgin, who was named the patron of Oruro’s Carnival. Since the priests had told the miners that El Tio was in fact the devil, they decided to honor their deity by performing in Carnival as diablos.

Photo Credit: Pablo Andrés Rivero

The demonic costumes, now an art-form in Oruro, are extravagant, frightening and heavy, featuring horned masks, velvet capes, shimmering breastplates and boots decorated with serpents. Due to the detailed work that goes into producing the elaborate handmade outfits, the costumes are expensive, retailing at several hundred dollars each.

Accompanying La Diablada are other dance groups representing various events in Oruro’s history including the Caporales, the Llameradas, the Morenadas, the Tobas, the Phujllay and the Tinkus.

Participating in Carnival is a huge honour to the Bolivian people. Each of the folkloric dance groups prepare months in advance, practicing their routines and getting fit for the 3 days of non stop drinking and dancing during Carnival.

UNESCO

On May 18th 2001, UNESCO declared Oruro Carnival a “Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity”.

Bolivian Life Quick Tip:

As voted the best way to travel around Bolivia and Peru, we highly recommend choosing Bolivia Hop as your means of transport. Their local guides have a wealth of knowledge about festivities and events that are guaranteed to be a trip highlight!

Dates of Carnival

Because carnival is timed to end exactly 40 days before Easter, the start date of the festival differs year to year.

These are the Carnival dates for the next 6 years:

Attending Oruro Carnival

Photo Credit: Szymon Kochański

- Travelers participating in Carnival will delight in the frenzied dances, colourful costumes, traditional drinks and upbeat music. Celebrations involve lots of water bombs, water pistols and spray foam so expect to get soaked regardless of which day you attend.

- Because Carnival is such a popular event, accommodation (see below for recommendations) is booked out months in advance. Travelers should plan to book as early as possible and expect to pay five times the normal price for a room. Also note there is usually a 3 night minimum when booking a room. If you do turn up in Oruro without a reservation there is a slight chance you can share a room in private house with dozens of other stranded people.

- Like any major festival around the world, crowds get rowdy and petty crime does occur, therefore it’s recommended to leave valuables at home and not drink to access. If offered the typical drink chicha, proceed with caution as it’s very strong and causes terrible hangovers.

- It’s also worth noting that Oruro is situated 3700 meters above sea level meaning travelers should give themselves time to adjust to the altitude, taking it easy, avoiding alcohol and drinking plenty of water. It also gets cold at nights so bring comfortable and warm clothing.

- While Carnival can be experienced on your own, keep in mind that this time of year is extremely chaotic so be prepared for things to go not according to plan. For this exact reason many people choose to experience Carnival with a tour company. Whilst more expensive, going with a tour offers piece of mind, comfort and guaranteed seats, something you may not achieve going on your own.

How to get to Oruro

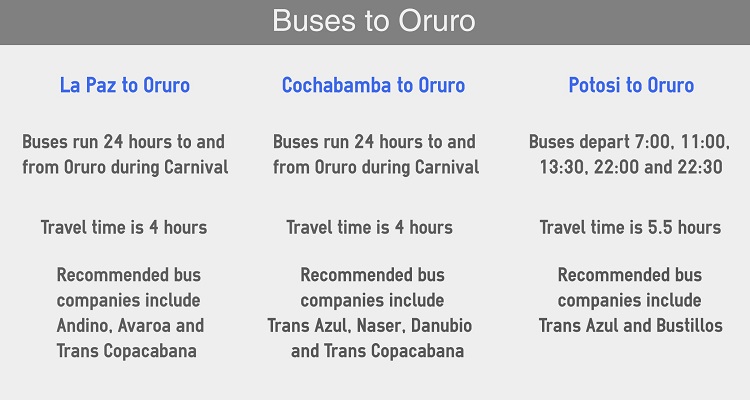

Oruro doesn’t have an airport, therefore the only way to get to Oruro Carnival is by bus. The following table outlines the main travel routes to Oruro, departure times and bus company recommendations: